A few weeks ago, we shared how we have taught our Bitswap nodes to jump. If you recall from that post, the content discovery range extension gained came at the expense of an increased number of duplicate blocks exchanged in the network. Already in that post, we reflected on potential ways of improving the issue with duplicate blocks to make more efficient use of bandwidth. One of our proposals was to use WANT message inspection and the peer-block registry (introduced in the prototype described here) to make content discovery more efficient by adjusting the degree of WANT message propagation with the introduction of relay sessions.

Equipped with the previous prototypes and the Testing Hardness, we had all the assets to explore this hypothesis of combining the Bitswap TTL prototype (described in this RFC) with the WANT inspection one (detailed here) and see what would happen. We rolled up our ResNetLabber sleeves, built a quick prototype combining both RFCs, and ran some experiments with our testing harness. The results were delightful!

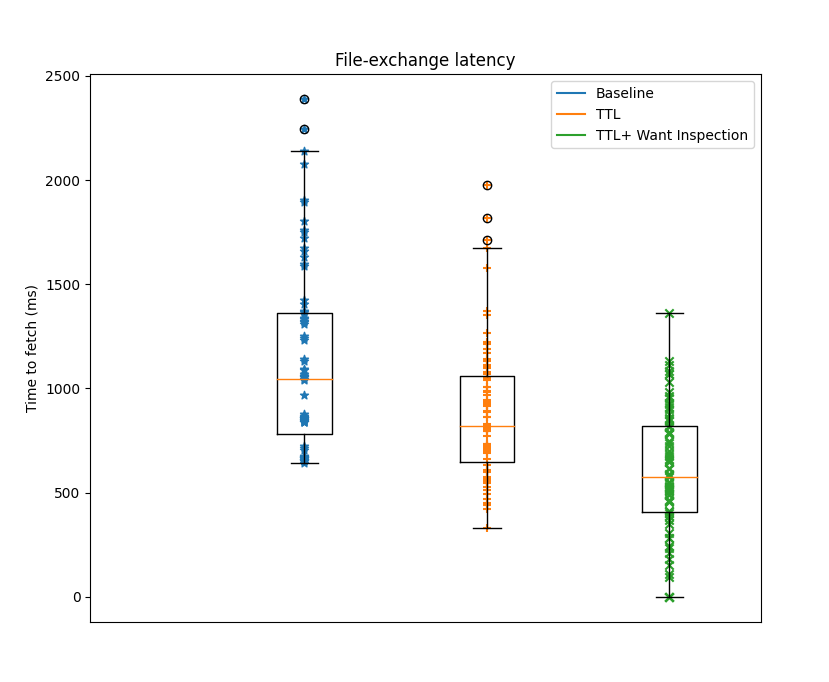

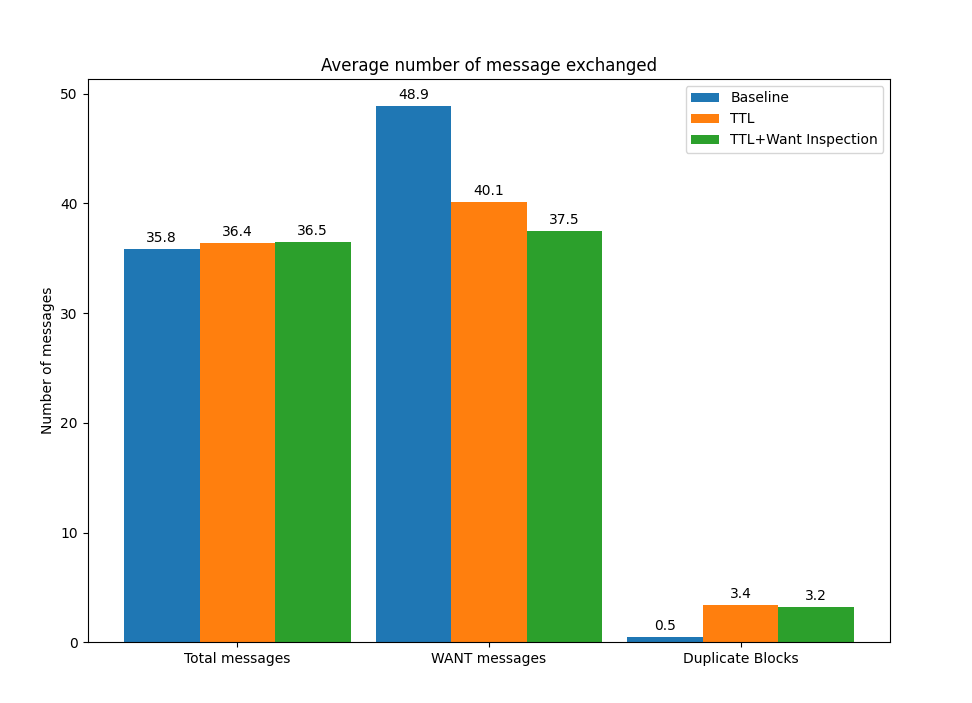

By allowing Bitswap nodes to inspect WANT messages received from other peers in the network we are able to perform faster lookups in sessions as well as ongoing relay sessions. With this implementation, we achieve an improvement in the latency to fetch the full file with a reduction of up to 12.5% compared to the vanilla implementation of Bitswap. At the same time, we reduced the number of duplicate blocks in the network by 10% compared to the TTL prototype.

Along with this new prototype, we also performed further experiments with larger files to understand the limitations of our “jumping Bitswap” proposal.

The contribution

With this prototype, we showed the value of leveraging the wealth of information gathered from previous network activity (i.e. WANT messages). We have proven that this information can be extremely useful in subsequent content discovery performance as previous requests are strong indicators of where the content lives.

Adding a TTL to the Bitswap protocol (in our previous contribution) offered nodes a way to discover content TTL+1 hops away before having to resort to the DHT. The TTL improvement also enabled faster retrieval of content from nodes TTL+1 hops apart, compared to vanilla Bitswap using the DHT. The new feature, though, came at the cost of additional overhead in the number of messages and duplicate blocks transferred through the network. After some further thinking, however, we realized that we could leverage this overhead in our favor to stretch the performance improvement introduced in our prototype even more.

Our rationale goes as follows: on the one hand, the fact that nodes can relay WANT messages from other peers increases the number of requests exchanged by a node. On the other hand, by enabling the inspection of WANT messages by Bitswap nodes, this information can be leveraged to populate their peer-block registry. The peer-block registry is a new data structure that we introduced in the Bitswap protocol which tracks for each CID the peer that has recently requested the content. This additional knowledge can be used by direct sessions to prevent them from broadcasting their WANT requests to every one of their connected peers. This knowledge can also be utilised by relay sessions to allow them to target peers with a higher probability of storing the content - this is where the TTL enhancement comes into the picture. Instead of selecting peers at random, the algorithm intelligently chooses to whom the TTLed WANT requests are forwarded.

Merging these two ideas enabled an improvement in the average time to fetch content by 12.5%, with a reduction in the number of duplicate blocks in the network by 10% compared to the previous TTL prototype.

Not happy with this, we decided to perform further experiments to understand the impact that exchanging larger files could have for our “jumping Bitswap” protocol. The experiments show that with an increasing number of blocks exchanged, the overhead from the number of duplicate blocks traversing the network can dwarf the improvements in the time to fetch content. This is a result of using symmetric routing to forward blocks through intermediate nodes (i.e. relaying blocks following the same path the request followed).

To solve this, we look to the use of asymmetric routing. Thus, when a peer storing the content receives a relayed request, instead of forwarding blocks through an intermediate peer, it establishes a connection with the requester and sends the block directly.

Prototype

You can find the code for this modified implementation of “jumping Bitswap” in this fork. Its operation is straightforward:

-

Every Bitswap node listens for WANT messages from neighboring peers and populates its peer-block registry with the CID and the ID of the peer sending the WANT message. This is done for every WANT message independently of its TTL.

-

When a client wants to find content, a new direct session is triggered in Bitswap. These sessions check if there are candidate peers that have requested the block recently by checking the peer-block registry, and, if this is the case, an “optimistic” WANT-BLOCK is sent to the three peers that requested the CID most recently (up to this point, we see the normal operation of this RFC).

-

If a node receives a WANT message with a TTL larger than zero, instead of forwarding the WANT message with TTL-1 to a random subset of d of its connected peers (where d is the degree of the relay session), it first chooses three candidates from the peer-block registry that have recently seen the CID (if they exist) and select the d - 3 peers left for the forwarding session randomly. In this way, the relay session is targeting peers that have recently requested those CIDs on behalf of other peers.

The use of peers from the peer-block registry to forward the requests from other peers increases the probability of intermediate nodes finding the content, hence performing faster discovery of blocks. Additionally, the fact that nodes may be looking for blocks on behalf of other peers makes the use of the information in the peer-block registry more powerful than in the baseline implementation of Bitswap.

Results

In order to explore the impact of this prototype, we repeated exactly the same tests from the TTL prototype evaluation. We repeated the experiment where 15 different leecher IPFS nodes requested different types of content from five different seeder IPFS nodes. Leecher and seeder nodes are not allowed to be connected directly, and they can only communicate through a set of passive nodes that neither provide nor request content from the network but instead run the vanilla Bitswap protocol. As was the case in our previous experiment setup, we used links of 100Mbps with 100ms latency between nodes, TTL = 1, and degree d = 10. For the peer-block registry, the number of candidate peers selected is n = 3.

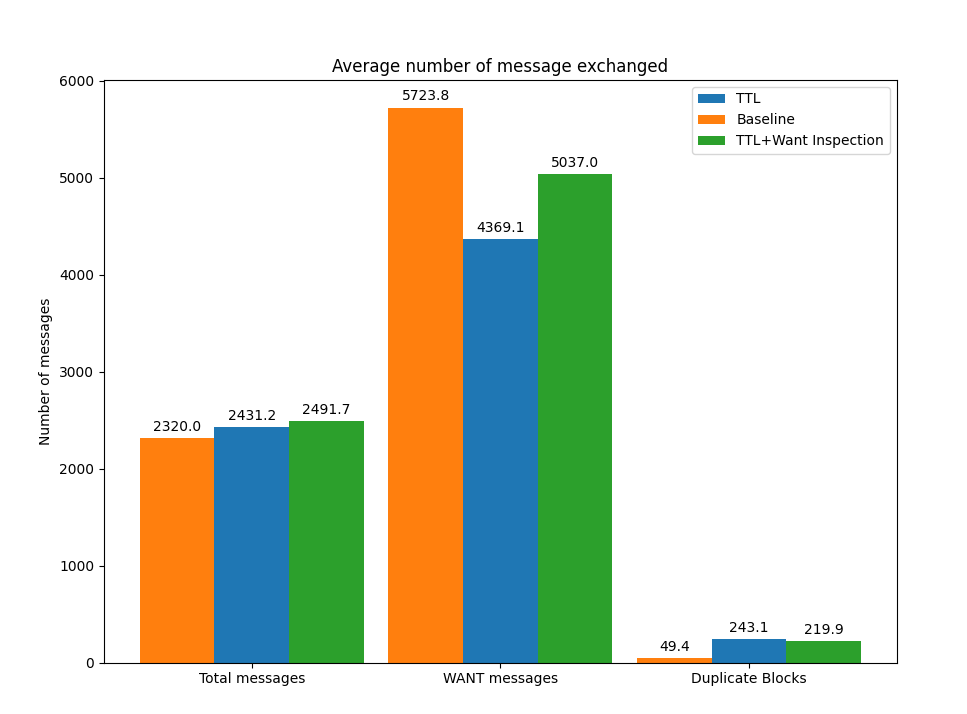

Figure 1: XKCD images exchanged by nodes in our experiment

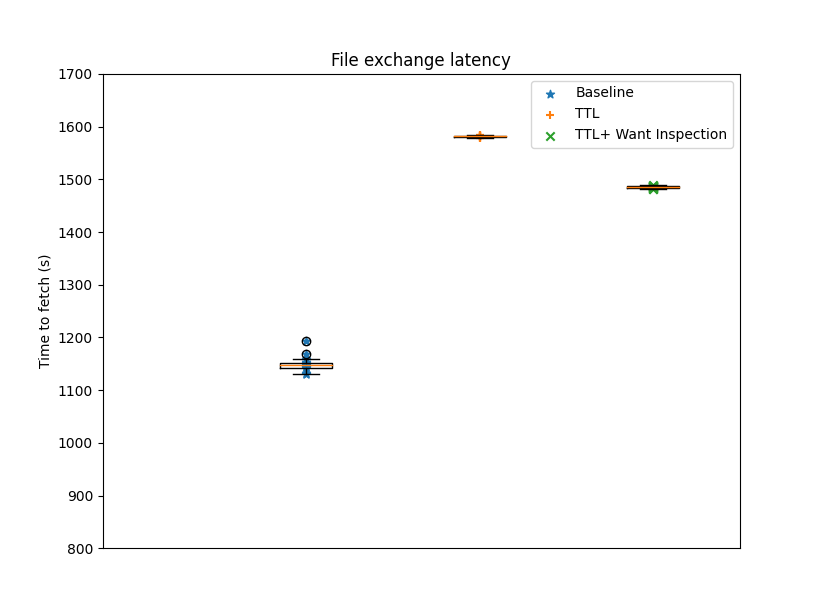

Exchanging small files

For the exchange of the small XKCD image file of 66 KB, we see an improvement in the time to fetch the image of 12%, with a slight reduction in the number of duplicate blocks and messages exchanged. The fact that nodes have a way to request the content from peers with a larger probability of storing it reduces the amount of messages required in both direct sessions and relay sessions. (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2: Time to fetch xkcd image

Figure 3: Number of messages exchanged for XKCD image exchange

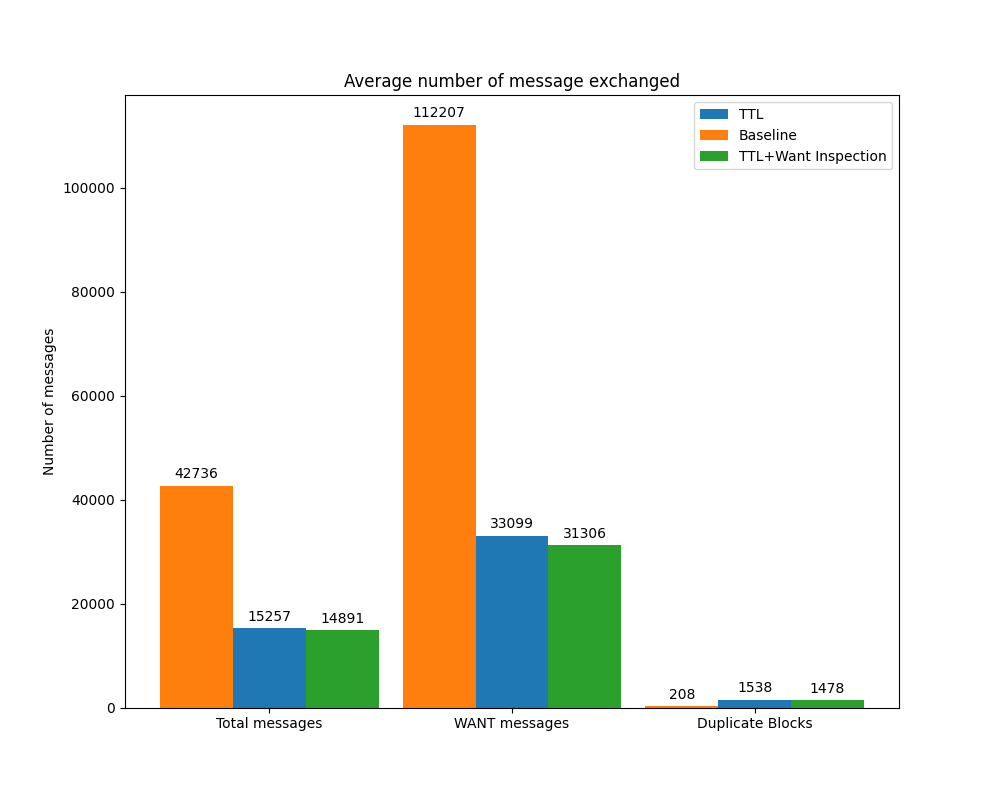

Impact on larger files

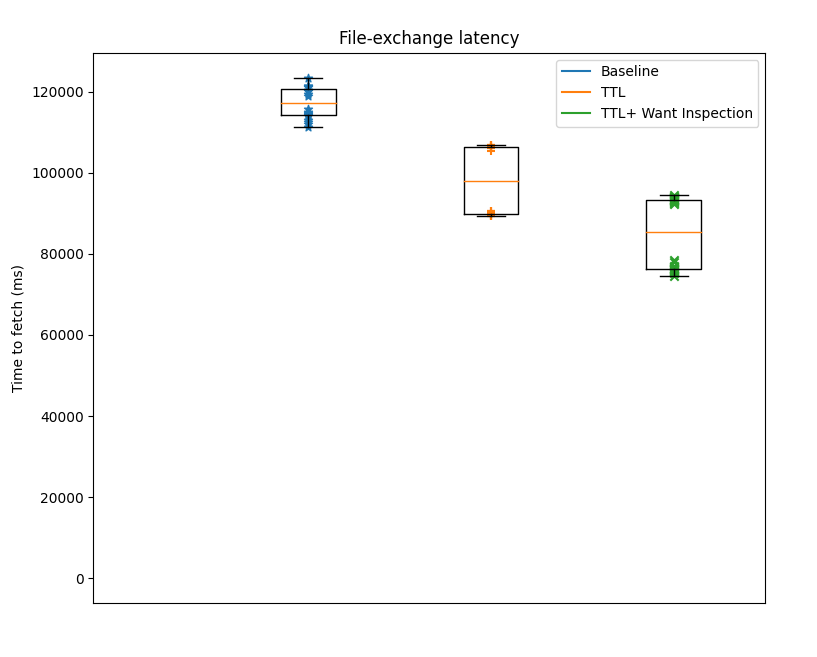

Repeating the experiment using 30MB files shows similar performance in terms of the time to fetch (i.e., an improvement of approximately 12%) and reduces the number of duplicate blocks in the network even further.

Figure 4: Time to fetch 30MB file

Figure 5: Number of messages exchanged 30 MB file

We went one step further and repeated the experiment for 150 MB files. The number of messages required for “jumping Bitswap” to discover and transfer the content compared to vanilla Bitswap is still significantly lower. However, the increase in the number of duplicate blocks originating from the TTL enhancement results in peers not being able to fetch content faster than vanilla Bitswap (see Figures 5 and 6).

Figure 5: Time to fetch 150MB file

Figure 6: Number of messages exchanged 150 MB file

Vanilla Bitswap performs a DHT lookup to discover the seeders storing the content. When it finds one, Bitswap establishes a connection with it, adds it to its session, and requests the rest of the blocks directly from this seeder from then on (without additional lookups).

For both versions of “jumping Bitswap” (with and without WANT inspection), even if a requester discovers the intermediate node, behind which is a seeder with the content, it still needs to request every single block of the content through those intermediate nodes (due to the symmetric routing approach used in the protocol). This results in a significant increase in the number of blocks traversing the network, with its subsequent overhead in peer resources.

Future Work: Asymmetric Routing

This limitation can be overcome using asymmetric routing to relay blocks to requesters. In this modification of the protocol, we add a source field, along with the TTL, into Bitswap messages. When a seeder receives a request for a block, it checks the source. If it comes from a peer that the seeder is directly connected to, it sends the block back. If this is not the case, and the seeder is not directly connected to the source, it establishes a new connection with the source and forwards the block back to the requester. From then on, leecher and seeder have an established connection between them, so that when the leecher needs to request further blocks of the content, it can send a request directly to the seeder without having to traverse any intermediate nodes.

Asymmetric routing enables “jumping Bitswap” to work in an analogous way to how it operates with the DHT. Asymmetric routing and the DHT are exclusively used to discover providers for the content, while the exchange of blocks is performed directly through a established connection. This minimizes the number of blocks and duplicate blocks that need to traverse the network in the exchanges. Furthermore, as was also the case for the symmetric routing approach, “jumping Bitswap” with asymmetric routing enables the discovery of seeders that are undialable for the DHT. The use of direct connections of intermediate nodes (used as relays) enables content discovery that is not possible through the DHT. In the asymmetric routing approach, after discovering the content, it is the seeder that proactively establishes a connection with the leecher, so, even if it is behind a NAT, the seeder will avoid many of the connection establishment limitations that can arise when using the public DHT.

Conclusions and more Future Work

This prototype stresses, even more than previously, the importance of using as much information as possible to perform smarter content discovery and retrieval. The use of a TTL field in Bitswap messages allows WANT messages to jump a few hops away, and this results in nodes receiving requests for content from peers not directly connected to them. Just inspecting these WANT messages from a few hops away provides nodes with additional information about where blocks may potentially be stored.

Additionally, the fact that relay sessions use a symmetric routing approach to forward WANT requests and blocks means that nodes do not need to establish additional connections, nor do they need to learn how to dial the peer that recently requested a block. Nodes know that if they send the request to the peer from which the inspected WANT message came, their own subsequent request will follow the same path to the initial requester.

Nonetheless, symmetric routing comes with trade-offs. When the files exchanged are large and composed of a large number of blocks, the overhead of duplicate blocks traversing the network may negate the time-to-fetch improvements of the “jumping Bitswap” protocol. While vanilla Bitswap has to do a single DHT lookup to discover a seeder and request the content directly, “jumping Bitswap” with asymmetric routing needs to discover the content through intermediate nodes for each TTL. To solve this, we propose (as future work) the use of asymmetric routing in “jumping Bitswap” for the relay of blocks.

A detail that might be overlooked is that symmetric routing can be useful when nodes are blinded from each other through NATs. Symmetric routing can be used as a way to relay the messages through NATs without having to resort to trasnports such as WebRTC and/or libp2p-circuit-relay to establish the relayed connections. We find these two approaches to be parallel to NDN and IP-based routing, respectively. Symmetric routing effectively routes data with knowledge by the intermediary nodes, while transport-based relays leverage tunnels and/or paths between nodes to deliver the content. Each approach offers different performance and caching guarantees.

Apart from the use of asymmetric routing, a few questions we ask ourselves after merging the want inspection and “jumping bitswap” prototypes are:

-

Can we optimize the way we select the subset of peers to whom WANT requests from relay sessions are forwarded? Can we use information about direct sessions (such as the latency, and peers included in each session) to make even better decisions? Is it worth tracking, in the peer-block registry, the TTL of the WANT messages seen so that we don’t only prioritize candidates that have recently seen the content, but also candidates that are fewer hops away (to ensure fast retrieval of blocks)?

-

Thinking about the configuration parameters of the protocol, what configuration of the degree (d) and TTL of relay sessions, and the number of candidates selected in the peer-block registry, leads to a better performance? Can we make these parameters dynamic in runtime, so that their values self-adjust based on network conditions, the peers available, and the probability that the nodes contacted have the block we are looking for? Would these improvements prevent us from having to adopt asymmetric routing? Even more, could “jumping Bitswap” implement symmetric and asymmetric routing, allowing peers to choose (or dynamically adjust) what approach to use at each moment?

-

Finally, can we take inspiration from how routing is done in fields such as NDN networks or traditional packet switching networks in order to optimize the relay mechanisms used to discover and forward content from peers to whom we are not directly connected in Bitswap?

After all of our explorations around “jumping Bitswap”, we have become convinced that the idea has great potential to reduce Bitswap’s burden over the DHT in the discovery of content. These are exciting ideas and exciting results that require further research to unleash all of their potential. If you want to join us in this endeavor of making file-transfers blazing fast, do not hesitate to reach out!