Increasing software update security through PGP-compatible threshold signatures

Whether we are aware of them or not, software updates and the systems that support them permeate the current software landscape. Given their pervasiveness, it should come as a surprise that software created to manage such updates, broadly referred to as package managers, still pose security concerns. Just within the last year, information security consultant Alex Birsan found a new type of supply chain attack on the Node package manager that he called a dependency confusion attack, wherein he exploited an issue with the way package names are resolved. At the time the issue was publicized, over 35 companies, including Microsoft, Apple, and Tesla, had detected this type of vulnerability on their network.

Package managers require communication channels, implicit trust from the user, and can download and execute arbitrary code from third parties. This makes them attractive targets for supply chain attacks, including but not limited to the dependency confusion attack mentioned above. In this article, we will be focusing on package manager security and will present our contribution to the space.

Current Security Considerations

In order to provide minimal security guarantees, every package manager must, at the very least, solve two problems: it must ensure software integrity, that is, the ability to guarantee that the software has not been modified between the time the developer publishes the bundle and the time the end-user downloads it; and it must provide software authenticity, some mechanism for verifying the identity of the developer who published the software package. In this model, which we will call the traditional model of package security, both guarantees are provided through digital signatures on package digests backed by centralized public key infrastructure.

One of the earliest systems implementing package signing is Debian’s Advanced Package Tool, apt, which can also be used as the key distribution mechanism by providing the debian-keyring as a central repository for all of the keys held by the Debian maintainers. More generally, early package signature schemes used the Pretty Good Privacy (PGP) standard for cryptographic software to generate and maintain their public and private keys, sign packages, and host them on publicly accessible, append-only key servers. It was also responsible for the trust model surrounding keys and signatures: the binding of a public key to a developer’s identity can be made locally and needs external verification to be trustworthy. PGP’s answer to the need for verification was the Web of Trust, a system wherein participants attach signatures to the aforementioned publicly available keys to indicate that the owner of the key is indeed who they claim to be.

A precursor to the public key infrastructure that powers the secure Internet, the Web of Trust has been used to great effect in multiple projects, but the adoption of PGP as a general solution to the problem has been hampered somewhat by its difficulty of usage. Even if it features as a contender for usage in newer systems, the response to such proposals has been lukewarm at best.

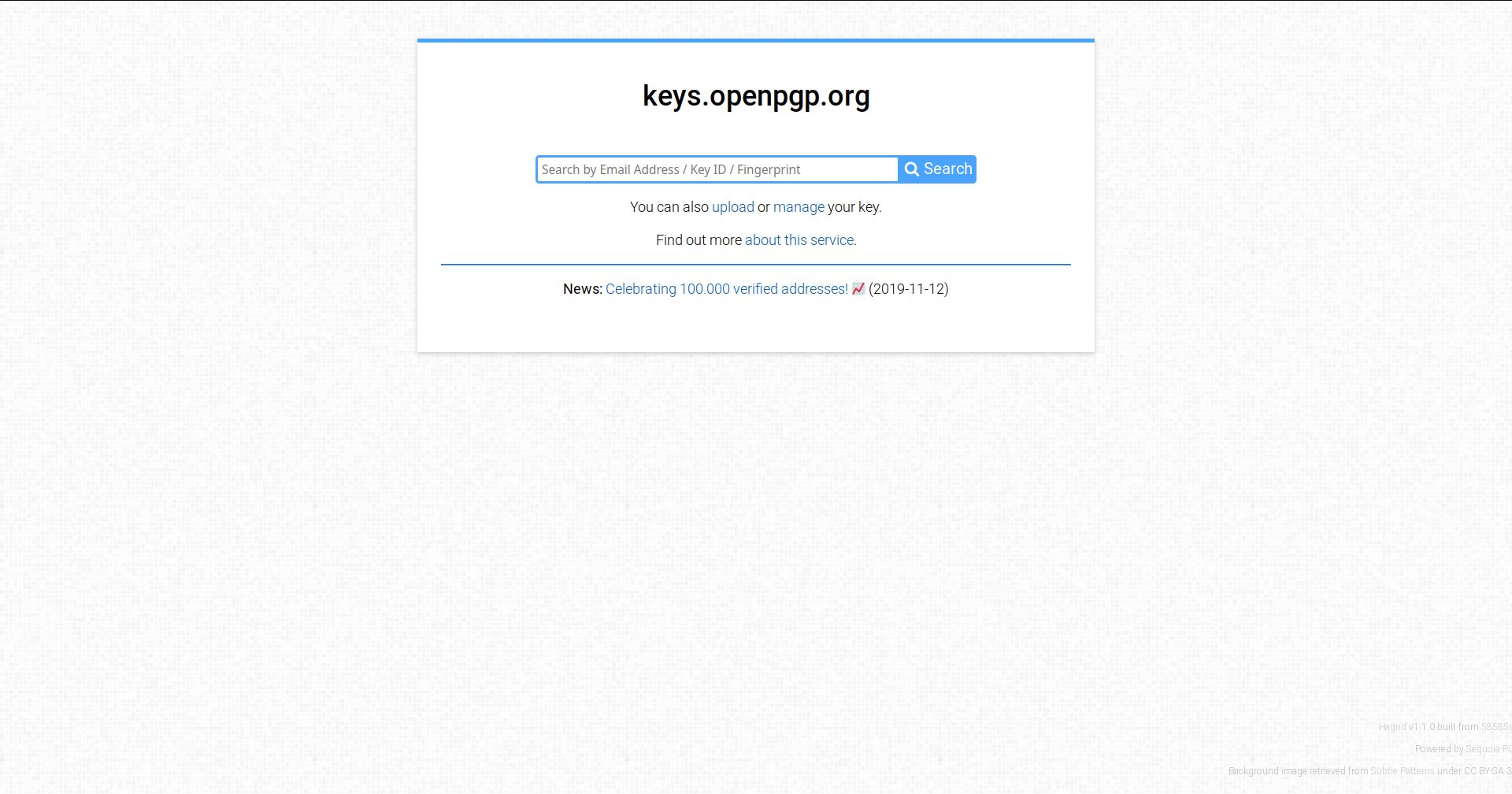

A web interface for a modern PGP key server: note that you still need to know the identity of the public key you are looking for

Later research into software update systems, often framed as research into package managers, has uncovered several implicit trust relationships within the makeup of these systems that attackers can exploit. In particular, the traditional way of securing a package does not take into account its security over long periods of time, during which the developer’s private key can get lost or stolen, nor does it make allowances for people joining projects and leaving them, whereby public keys must persist if the user requires them to verify older signatures. Software update systems were also not designed to reveal such changes to the end-user, always presenting a single instance of the security via the singular software signature (if signatures are indeed employed) and never providing a holistic picture. Another, massive, problem is that, even with open-source software, verifying that the source code corresponds to a particular binary is not a straightforward task.

The last challenge might surprise readers, but fundamentally the end-user will rarely have the resources or the capacity to verify the source code of the solution against the binaries they receive. While traditionally a problem with closed-source packages, open-source projects like the Tor browser require a whopping 40 hours to build on consumer hardware, making verification impractical at best. At the same time, the common formulation of the binary-source correspondence puts the onus of testing onto the user, requiring them to conform to the security goals of the platform. It also demands of the user the time and willingness to get into the weeds of building software and trawling through the inevitable build errors that occur when some dependency is not detected or is out of date, among other equally fun problems.

Finally, when seeking to improve package manager security for the end-user, we must ask whether the responsibility of verifying binary-source correspondence should fall to the user. A better solution would be to ensure that the developers can carry out this sort of verification by going through the proper auditing procedures to verify that no malicious code has been introduced into the codebase. There truly is no better way to do so than through the very version control systems that form an integral part of the development process. When the developers of a software project use a version control system for collaboration, each change becomes loosely associated with a user, and every change is added to the publicly queriable history of the project. The version control system is also the point of communality for developers working on different projects with different tooling and programming languages.

Our contribution: Dit

It is within this context that we place our project, Dit, a wrapper around Git that uses recent advances in collaborative signing to demarcate releases. This requires consensus amongst a group of developers to sign a version tag, integrating with the current Git signature verification scheme using PGP, and thus adding an explicit point in the development workflow where a developer may want to audit the code for changes to ensure nothing malicious has been introduced.

Threshold signatures and the protocols that generate them are novel tools first proposed by Gennaro et al. in their 2001 paper. Although impractically expensive in their earliest incarnation, they proved a good foundation for subsequent work sparked by cryptocurrencies wanting to eschew private keys in parts of their infrastructure. Threshold signatures, at a very high level, are generated by a set of two protocols: a key generation and a signing protocol. For the key generation, all of the parties involved collaborate to collectively generate the public and secret keys, at which point each participating developer gains a portion of the secret. Before generation, a threshold number is chosen; this corresponds to the number of developers needed to recreate the key. The signing protocol then uses a threshold of the developers to recreate the key and sign the release in a manner analogous to the way the version control system does it. Finally, putting it all together, the signature generated on the tag is indistinguishable from that generated via a normal digital signature algorithm, giving us verification essentially for free.

While existing protocols require all of the participating developers to be online at the same time (there is some talk about improving this situation), the conveniences of threshold signatures cannot be overstated for this use case, namely: because no single developer has the complete authority to authorize releases, we eliminate the problematic single point of failure; the participants avoid having to use an external tool to generate and maintain their public-private key pair; and, upon detection of a compromise, developers need simply participate in a lightweight key rotation protocol to refresh their shares, with little need for external infrastructure.

The threshold signing approach also changes the trust model. As opposed to the attacker succeeding when they compromise a single developer’s private key to create malicious releases, we assume an adversary that wants to insert a malicious payload, like a script to steal from local Bitcoin wallets, needs to obtain at least a threshold of shares to do so. Thus, we do not trust any developer with more than a single share (though the key generation protocols would work with such an approach and some libraries do implement it) and require that every developer has a chance to review and reject changes happening at release time.

In providing these changes, Dit creates a wrapper that calls to the underlying Git executable for version control operations and local repository information, adding two more operations invocable by the user. At the start of a project, the lead developer can create a Dit configuration file at the root of the Git repository to indicate the project name, the mode of communication used by Dit clients, and any supporting information, such as a server address, needed for the communication. The latter points merit further mention: the threshold signature protocol Dit uses does not impose many constraints on how protocol participants communicate, as long as there is a way to send the same message to every party (a broadcast) and for participants to communicate in a pairwise manner. This open-endedness has allowed us to explore different trade-offs.

For development and testing, we used a centralized HTTP server as a central hub through which all communications are routed—an approach well-suited for local observability, ensuring liveness, and one that could use its centralization to test out various policies on how to handle malicious activity within the protocol’s scope. At the same time, HTTP as a protocol might be suboptimal in cases of poor or intermittent network connectivity; in this case, Dit would have no trouble supporting parties communicating via some peer-to-peer protocol or piggybacking on other systems that were not explicitly meant for communication (one such possibility is IPFS; supporting it is within the roadmap but did not get completed in time).

To achieve these goals, Dit adds two subcommands, keygen and start-tag. The former is used to initiate the key generation, with all of the participants taking part. The same operation also signs the outputted public key to conform to the OpenPGP standard, allowing the developers to distribute the key how they see fit and use Git itself to verify that the tag signature is legitimate.

Dit key generation with server backing

The second of the two commands, start-tag, mimics the semantics of git tag while adding several indicators to show that the tagging is a collaborative effort.

Dit producing signature on tag

The envisioned use for Dit is to alias it under the git command (we provide action parity when in an initialized repository) and to use it as part of the regular development lifecycle until a protocol is initiated. The only other changes required for its implementation would be an additional tag verification check on the side of the continuous integration platform of choice.

Dit shows that it is possible to augment version control systems as part of the security model surrounding software updates—with minimal impact on development workflow. Although Dit is fully-featured enough to start experiments on workflow integration, it would be well served by further investigation on elements like the dependence on a central server to route communication and ensuring a good user experience that does not detract from a developer’s primary task.

*Author’s note: I would like to thank Philipp Jovanovic and Nicolas Gailly for their kind guidance with my master’s thesis, as well as all of the wonderful folks at Protocol Labs for their support.