We’re two materials scientists here at Protocol Labs, and we’re working to improve the electricity grid.

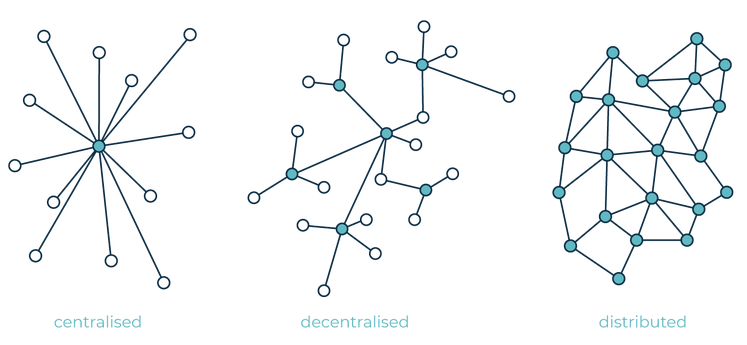

Why, you may be thinking, does a distributed file storage company have a project related to the energy grid? Part of Protocol Labs’ mission is to “explore the future of decentralization and examine the infrastructure limiting what you can do with technology”. The grid is definitely decentralizing, and it’s definitely limited by technology – so we want to bring some of Protocol Labs’ expertise in distributed systems to bear both on the grid as it exists now as well as how it will develop in the future.

Before we get into the nitty-gritty of how we’re doing that, though, let’s explore a few things:

- the grid itself and its core functionality;

- the concept of “transactive energy”;

- how you can solve an optimization problem as complicated as an entire electrical system; and

- the tools we’re using to do our research.

The physical grid

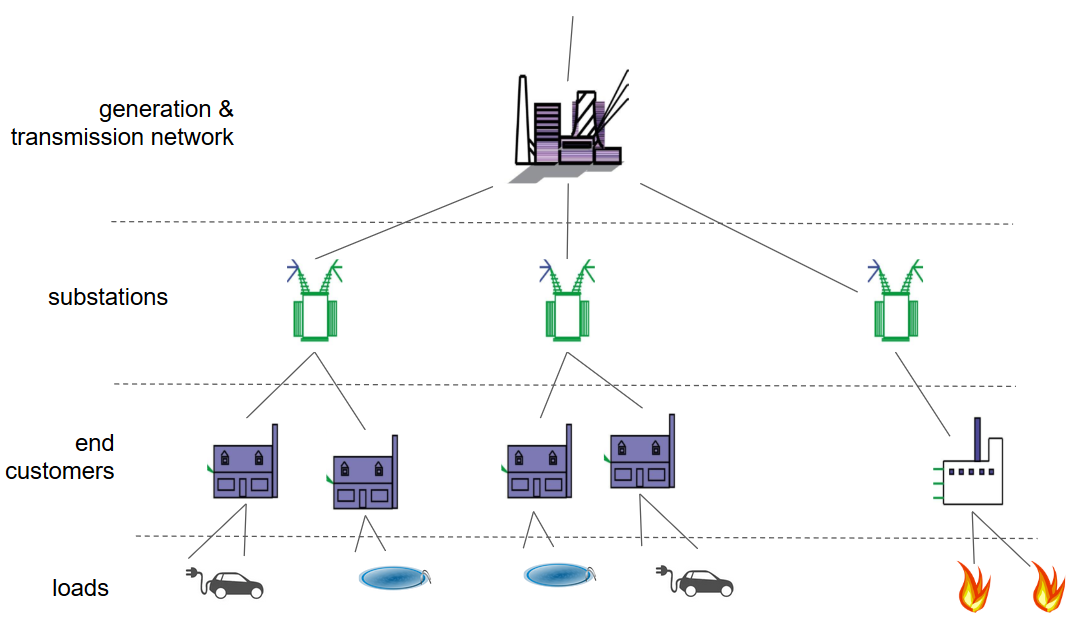

The U.S. electricity grid – and we’ll be focusing on just the U.S. grid for now – is a behemoth. There are about 10,000 utility-scale power plants in the United States [1] (and that doesn’t count any behind-the-meter power generation, such as solar panels on individual homes). Together, these power plants produce about 4 petawatt hours – that’s 4 trillion kilowatt-hours (kWh) – of electricity every year, which is enough energy to power a normal kitchen microwave for 500 million years. (The curious may enjoy a number of interactive maps illustrating where these plants are located, what type of fuel they use, and how much power each produces.)

Those 10,000 power plants transport power over 160,000 miles of high-voltage transmission lines to about 60,000 substations [2]. Power is stepped-down to a lower voltage and transported along an additional 6 million miles of distribution lines to power the approximately 150 million buildings in the United States – at a constant, stable 110 V and 60 Hz for our everyday needs.

The regulated grid

Electricity lines are the classic example of a natural monopoly – because space is limited, we don’t want multiple companies all putting down their own electricity lines. But because we rely so heavily on constant access to low-cost and high-reliability electricity, a number of different levels of government regulate not only that natural monopoly, but all aspects of electricity production and distribution. Local, state, and federal government all have a hand in what technical standards must be followed, what given proportion of energy must be renewable, who’s allowed to produce electricity and how much they’re allowed to charge for it, and how to make sure that we’ll still have enough electricity ten, twenty, and thirty years from now [3].

A functionally-defined, invariant architecture for the grid

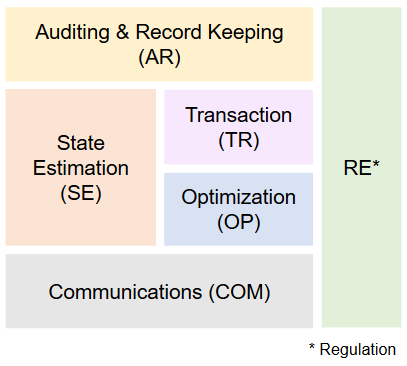

Alan has boiled the grid down to a set of six core functions that we’ve termed the grid’s Functionally-Defined, Invariant Architecture (FDIA). It includes these six core functions:

- State Estimation (how power is actually flowing on the grid);

- Optimization (how to supply power to keep it as efficient and inexpensive as possible);

- Regulation (what the grid and actors on the grid are allowed to do);

- Transactions (who bought how much power and how much it costs);

- Auditing and record keeping (what actually happened with the grid); and

- Communications (because there are a lot of parts of the grid that need to talk to each other).

The idea is that though any given module may have different specific goals, its function as a module will remain the same. Thus, one locality might one day allow net metering or demand response; and another (or the same locality, at a different time) might not. Swapping between the two modes should be as straightforward as swapping out one regulatory module for another with a few keystrokes.

(We’ve made this sound much simpler than it actually is; don’t worry, this is going to be the topic of its own blog post soon.)

Not your average box of chocolates

Why does the grid need to decentralize with distributed generation?

Good question! In theory, there’s no reason why a utility couldn’t control millions of individual solar panels and batteries. In practice, though, centralized grids handle distributed generation weirdly. There are a few ways this is true, but my favorite examples are net metering and demand response.

Net metering is the idea that, if I have a solar panel on my roof, I can sell any excess electricity back to my electricity provider for the same price they charge me. Seems reasonable enough, at first blush – until you consider that I don’t have any staff, I don’t pay for any distribution wires, and the utility doesn’t need (or really even want!) my power at all. But hang on, you might say – it’s not fair to judge net metering that way, since it’s effectively a subsidy to get the cost of solar down. But that’s exactly my point – it’s a clever way to subsidize solar panels and solar power, but it’s a terrible way to run a market, especially once you’ve reached the point where you have a lot of solar panels producing electricity all at the same time in the middle of the day.

Demand response is the idea that lowered electricity demand is identical to increased electricity generation – and should be paid accordingly. That is, if I’m a utility, and my grid is short 10 MW of power, I can either turn on a 10 MW power plant or turn off a 10 MW factory (either by asking nicely or by paying them. In both cases, the grid ends up with exactly as much power as it needs. Demand response, as it’s been formalized by FERC, is the idea that the 10 MW factory is legally entitled to receive the same amount of money I would have paid to turn on that 10 MW power plant. Again, this is a very clever subsidy for what usually ends up being load shifting or load shedding; but it still seems oddly close to protection money: “Hey, nice grid you got there – shame if it were to break because I wanted to use my normal amount of electricity…!”

There are other disadvantages to centralized grids, of course; the Wall Street Journal reported in 2014 that disabling 9 carefully selected substations could create a nationwide blackout [4]. Many readers will recall the California wildfires that PG&E tranmission lines started in 2019; they may not know that their high-voltage transmission lines were starting an average of one fire per day over six years [5]. At the same time, though, decentralized grids have problems of their own, too; so we’ll hold off on discussing those for now.

So how do you optimize a grid with distributed generation?

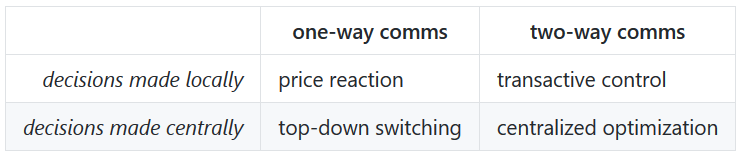

There are a few ways to optimize a grid with distributed generation, depending on what you’re looking to optimize. Take a look at the chart below: if you value everybody being able to completely control their own electricity usage, you’ll probably prefer that local decisions are made locally. If you value finding the absolute most-efficient global solution (i.e., minimize the amount of electricity used, or the amount of money spent), you’ll probably prefer that local decisions get made centrally – that is, a utility decides who gets exactly how much electricity.

Punnett squares: not just for Mendelian genetics. Adapted from [6].

The other dimension of the square is the type of communication present: you can have one-way communication from the utility to end users of electricity, or you can also flow information back to the utility (and have two-way communications). There are a few easy ways to understand these scenarios.

For example: let’s say I’m PG&E during the California electricity crisis, and all of a sudden there’s more electricity demand than I can supply. If I can use a price signal to tell everybody that the price of electricity has increased, then people can choose how much electricity they want to buy; and I can keep increasing the price until demand has dropped, and the grid remains stable, even if people are grumbling about it.

But if I’m PG&E and I can’t raise the price – either because state regulators have disallowed it, or because customers don’t have the ability or desire to quickly and carefully modulate their electricity usage based on price signals (or both, as was actually the case) – then I’m stuck with top-down switching, which, in this case, means rolling black-outs.

But let’s say that hardware’s gotten cheaper, and suddenly I can send messages to all of the devices on my grid and those devices can send messages back. I can then run an auction based on how much power I have available, and give out power according to its rules. This format is centralized optimization; it will typically get you much closer to a globally optimal solution for power usage and/or cost, but it will also remove a fair amount of local decision-making power.

With distributed generation, though, things get even more interesting. A neighbor with a solar panel may want to sell excess power generated during the day directly to a neighbor with an electric car – and to do it for half what the utility would charge. This is the promise of transactive energy; and with a big enough marketplace, bids could be flying back and forth between various devices all of the time. It’s hard to tell how efficient it woud be compared with centralized optimization, but it gets pretty close, and it has the potential to be cheaper and more resilient as a framework, as well as restoring decision-making power to individual electricity users.

Sidebar: ISOs & LMPs

ISOs are Independent System Operators; they’re the organizations that run the transmission system in dense, complicated areas of the grid, and there are currently nine of them in North America. LMPs are Locational Marginal Prices, and they are a way of pricing wholesale electric energy to reflect its value at different locations, accounting for the varying patterns of load, generation, and the physical limits of the transmission system over time. As a concept, they resemble how transactive energy might be priced and traded, but at the transmission-level.

A key difference is that the ISO is optimizing for something called security-constrained economic dispatch, which is a framework to use lowest-cost resources, including demand response, while still keeping some redundancy in place (in case a power plant or transmission line suddenly fails).

So why aren’t we using transactive energy?

Good question! There are two answers: firstly, because the current system still mostly works (and if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it); and secondly, because finding the globally optimal solution for millions of buildings and power plants, all trying to talk to each other all at once, hundreds of times per day, is a computationally intractable nightmare of the highest order for a single entity to run. But that doesn’t mean we can’t get clever about it by splitting the problem up.

Here’s how we get clever. Adapted from [7].

Splitting the problem up

The basic idea is that you split a big problem up into a lot of smaller problems (“decomposing” it), and by solving each of the smaller problems, you also solve the big one.

Say I have a big picnic with a lot of tables for buffet lines, and 500 apples to give to 1000 people, exactly 500 of whom like apples (and, for the sake of argument, get really, really upset if they don’t get one). There are a couple ways I can try to set up the picnic to ensure that everybody who wants an apple gets one:

- Put all the apples in one buffet line. All the apples are at one table, and I can ask everybody if they want an apple, and give them one if they do. Because there are 500 apples and 500 people who like apples who go through this one line, everybody who wants an apple can get an apple – the globally optimal solution – but boy howdy, it takes a lot of time, and the picnic is over before everybody gets through the line. (That’s what it means to be “computationally intractable”.)

- Put apples in multiple buffet lines. I can also set up ten tables with fifty apples each, and then randomly assign 100 people to each table to get their apple. It won’t make everybody happy – it’s pretty likely that at least one table will have more than 50 people assigned to it who wanted an apple, and so at least one apple is wasted and one person is upset – but it’s so much faster that I’ll probably still prefer this method over the single buffet line.

The “one buffet line” is, of course, the non-decomposed problem; and the multiple buffet lines represent the “decomposed” problem (specifically, decomposed into ten sub-problems: one for each table). What this example demonstrates is primal decomposition. This can get a lot more complex – for example, how would I divide the apples per table if I had different numbers of people per table? or if there were different types of apples that people liked? – but the basic idea is that I choose the number of apples to give to each buffet line, and each table then has to figure out whether or not people assigned to that table get an apple.

Splitting the problem up better

But there’s another way to handle the problem, called dual decomposition. In dual decomposition, the master problem sets the cost for a resource and allows each sub-problem to decide how much of the resource it wants at that cost. That is, instead of allocating resources directly as in primal decomposition, the master problem sets the pricing strategy for the sub-problems.

Let’s see how that would play out at the buffet lines at our picnic.

I still have ten tables with buffet lines; each still has 100 people; and I have 50 apples in ten baskets. But this time, before I put apples on the tables, I give the servers instructions: “Okay, everybody, listen up. I’m not sure why, but these folks get really upset about not having an apple when they want one, and we want to make sure that nobody is upset. Everybody do a quick poll of the folks at your table to see who wants an apple, and then let me know how many you need or have left over.”

Everybody polls their tables – and it turns out that seven tables want exactly 50 apples; one table wants only 47 apples; one table wants 52, and the last wants 51. I quickly move the apples around in the baskets accordingly and only then put them on the tables. This time, everybody at the picnic who wants an apple gets one – and it’s still a whole lot faster than the single buffet line!

In both the primal and dual decompositions of the picnic, the goal is to minimize the number of unhappy people. In the primal decomposition, though, I directly chose how many apples each table got in order to meet that goal. In the dual decomposition example, I gave each server the cost function directly (i.e., “minimize the number of unhappy people at your table”), and they told me how many apples they needed to do so. The astute reader will also note that the primal decomposition case didn’t really require two-way communication; but the dual decomposition case did.

Right now, the energy grid is mostly communicating in one direction, and the optimization it’s doing, insofar as we can call it that, is done centrally; locational marginal prices (LMPs) are a sort-of dual-decomposition solution at the transmission level. But as hardware becomes cheaper, as microgrids proliferate, and as smart meters get smarter, there will be more and more two-way communication on both the transmission and distribution aspects of the grid. That means – with a little luck and a lot of elbow grease – the grid will be able to use some of these more powerful ways of splitting up problems.

(For a more formal description of primal and dual decomposition, and how layers themselves can be used for decomposition, we highly recommend the excellent paper by Chiang et al [8].)

Laminar hierarchical coordination

Note that we’ve so far avoided the discussion of how we chose our sub-problems (i.e., why did we choose ten tables – or why did we choose tables at all? Why didn’t we ask for a few volunteers to walk among the crowd handing out apples?).

In an electricity grid, the nature of the distribution grid itself maps very closely to the dual decomposition solution we’d like to employ.

If you turn your head and squint, the power grid looks almost exactly like the ‘decentralized’ network in the graphic above.

It’s not too far from where things are today. Houses control how much electricity their devices use; and substations deliver (but do not price) electricity to houses. Generators sort-of already price electricity for substations (intermediated through utilities); that’s the whole idea behind locational marginal pricing.

And if that top generation/transmission node decomposes its optimization problem into subproblems, one for each substation; and if each substation decomposes its optimization problem into subproblems, one for each house, or microgrid, or factory; and each of those – well, suddenly, we’ve optimized the grid.

I’d like to point out that we’re far from the first people to talk about splitting the grid up this way; Taft pointed out in 2016 that laminar hierarchical coordination lends itself particularly well to the electricity grid [9], and has done a lot of work on it since. Nevertheless, we haven’t found a lot of people implementing it, which is why we think it’s promising to do ourselves.

VOLTTRON

I’m sure the writers of this software enjoyed, as I did, the hit 90s animated show “Voltron”, about a giant space robot defending the universe; but the focus of VOLTTRON™, software created by Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) is even cooler: microgrid control!

It’s funded by the U.S. Department of Energy, and it’s entirely open source and free for commercial use. It’s Linux-based (it can run on a Raspberry Pi!), has versions written in Python 2 and 3, it’s web-accessible, and it supports easy development of (and communication between) multiple independent “agents”, which are small programs that have specific tasks within a microgrid. These agents’ tasks can range from the simple (turning on and off a solar panel’s inverter) to the complex (predicting solar panel energy production using weather data).

All of these features make it ideal for us to prove out our functionally-defined invariant architecture (FDIA) – we can represent each of FDIA module as an individual agents within VOLTTRON™ (note that the communications module is taken care of by the VOLTTRON™ message bus).

So what are you actually doing with everything?

First, we’re simulating a bunch of individual loads using a standard IEEE feeder on a single VOLTTRON instance. We’re implementing time-of-use pricing and demand response as an example of capabilities that can be easily defined with a regulatory agent. Next, we’ll be connecting several VOLTTRON instances together and pretending we’re a small ISO, controlling how much power is flowing between each VOLTTRON instance, using dual decomposition and laminar hierarchical coordination to control the whole setup. We’re hoping to demonstrate that each instance is using the same FDIA with only small changes to the modules each is using. We’ll be publishing our results and taking it to regulators and utilities, as we refine our model and make the grid as robust as we can make it.

Thanks for reading – and keep an eye out for future posts!

Sources

- “How many power plants are there in the United States? - FAQ - U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA),” 2019.

- W. Warwick, T. Hardy, M. Hoffman, and J. Homer, “Electricity Distribution System Baseline Report,” PNNL-25178, 2016.

- I. Chernyakhovskiy, T. Tian, J. McLaren, M. Miller, and N. Geller, “U.S. Laws and Regulations for Renewable Energy Grid Interconnections,” NREL/TP-6A20-66724, 2016. doi:10.2172/1326721.

- R. Smith, “U.S. Risks National Blackout From Small-Scale Attack,” Wall Street Journal, 2014.

- M. McFall-Johnsen, “Over 1,500 California fires in the past 6 years including the deadliest ever were caused by one company: PG&E. Here’s what it could have done but didn’t,” Business Insider, 2019.

- K. Kok and S. Widergren, “A Society of Devices: Integrating Intelligent Distributed Resources with Transactive Energy,” IEEE Power and Energy Magazine, vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 34–45, 2016, doi:10.1109/MPE.2016.2524962.

- P. Baran, “On Distributed Communications,” The RAND Corporation, RM-3420-PR, 1964.

- M. Chiang, S. H. Low, A. R. Calderbank, and J. C. Doyle, “Layering as optimization decomposition: A mathematical theory of network architectures,” Proceedings of the IEEE, vol. 95, no. 1, pp. 255–312, 2007, doi:10.1109/JPROC.2006.887322.

- J. D. Taft, “Architectural Basis for Highly Distributed Transactive Power Grids: Frameworks, Networks, and Grid Codes,” PNNL-25480, Jun. 2016. doi:10.2172/1523381.